12 months ago the Adelaide Hills magazine published an article about David’s quest to find Grandmasters. Please see the text of the article, wonderfully written by James Howe below:

12 months ago the Adelaide Hills magazine published an article about David’s quest to find Grandmasters. Please see the text of the article, wonderfully written by James Howe below:

David Koetsier believes there are young chess-playing superstars waiting to be discovered in the Adelaide Hills. Trouble is, he says. They’ve always been overlooked by a nation more obsessed with ball-games. James Howe talks to the Grandmaster who believes teaching chess can be as formulaic as teaching spelling – and that a touch of Asperger’s can mean a path to glory…

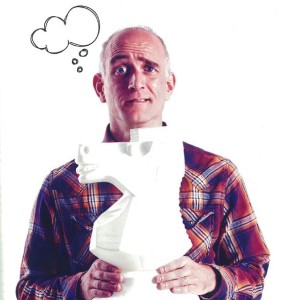

I hear him before I seem him: a loud, musical voice ricocheting off the concrete floor of the Udder Delights cheese cellar. “Hi, hi! Yah, I’m going to need to get a coffee”. Presently, David Koetsier round the corner with a cappuccino; he’s a small, tidy man in an orange flanno, buttoned nearly to the Adam’s apple. He parks himself opposite me, bobbing his head and grinning broadly in greeting.

He begins to tell me what he plans to do in the Hills. “You have to understand in the last 40 years in Australia, there have been only four Grandmasters. Only four!” He shakes his head, contemplating a figure he hasn’t quite dealt with during his nine years in Australia. In short, David plans to make a lot more. David was born in Holland, where there are 150 Grandmasters (a title conferred by the World Chess Federation) and everybody plays. But David says he started late – at age seven. “I played chess because I was bored out of my brains at school.”

As fate would have it, he was good. Really good. By 12, he was travelling Europe with professional players much older than himself. He made good money doing it, too. “If you can pay your way through uni, you can imagine the figures,: he says. Today, when he goes home to Amsterdam, kids stop him in the street for autographs. When he pulls out a chessboard, he gathers huge crowds. Such is the reality of being a chess star in Holland, where the sport rates second only to soccer in popularity. And David was a star.

But in 2005, when David arrive in Adelaide, he was unknown. There was, he says, no real chess scene at the time. I protest at this, recalling a lively chess program at my high school. St Ignatius College, back in the early 2000s. “Ahh St Ignatius. Yah, yah, we played them last year.” He says, leaning back to sip his cappuccino before briskly dabbing his lips with a paper napkin. “That, for me, is not a level of chess. There is a difference between playing chess and just messing about with chess pieces.”

But in 2005, when David arrive in Adelaide, he was unknown. There was, he says, no real chess scene at the time. I protest at this, recalling a lively chess program at my high school. St Ignatius College, back in the early 2000s. “Ahh St Ignatius. Yah, yah, we played them last year.” He says, leaning back to sip his cappuccino before briskly dabbing his lips with a paper napkin. “That, for me, is not a level of chess. There is a difference between playing chess and just messing about with chess pieces.”

David isn’t arrogant when he placed my school in the latter camp; he’s being honest. He’s European, and is accustomed to European chess. Australian chess, by comparison, is found to be wanting. “I’m still working at the European standard.” He says. “Because if you lower your standards, then you as a parent will say, ‘oh my son is doing great!’ But he isn’t”

Instead, David plans to raise a generation of true-blue, home-grown, Australian Grandmasters. And he believes he can do it. In Hahndorf, he says, there are already more kids playing chess than soccer. Many of these have real promise. “There are geniuses walking around here. They’re walking around! But you’ve got to look for them. And nobody’s looked for them before.” But he’s looking. Formally educated as a medical physicist, David has discarded his career in this field to allow him to dedicate all of his time to the quest for Grandmasters. He has even let go of his chess career, because the 40 hour-plus playing week of the professional was incompatible with coaching.

Today, all his time is absorbed in travelling between Hills schools, teaching chess to students. He squeezes his lessons into gaps before classes, during lunch and after school. The take-up, he says, has been astonishing. “Something is really happening,” he says. “Kids are coming from everywhere.” Although David has started his search for Australian Grandmasters in the Hills, he doesn’t expect it to end there. “My aim is to put not only Hahndorf, or Adelaide on the map, but also to put Australia on the map,” he says.

But can David really teach people to be chess champions? Or do you need to be born one? The answer, he says, is a little bit of both. Although teaching chess is as formulaic as teaching maths or spelling, it pays for a pupil to have the right kind of temperament. The first thing to look out for, when it comes to chess, is a little bit of Autism. “Asperger’s-related students, mostly, are really good at chess, because they can think for 10 hours,” he says. A chess champion is likely to be someone who has felt at odds with a culture that elevates ball games, says David, “and there are a lot more chess players than footy-players, trust me.” But while natural chess players may form the majority in Australian schools, they haven’t traditionally had many opportunities for glory in the sporting arena. This is where David comes in. “I make a slot for them,” he says. “Teachers and principals find it amazing how many children don’t have a slot. Now they say, ‘Why didn’t we do this thing years ago?”

One reason is a dire shortage of teachers. Geniuses with Asperger’s make excel lent chess players, but they’re not usually great at holding the attention of six-year-olds. So does David has Asperger’s? Absolutely he does. But in his case it’s an ingredient in a rare personality cocktail. “I am different because I have Asperger’s, too – but I am sanguine.” It’s the perfect mix: the Asperger’s lends an obsessive concentration needed to be a brilliant chess player, while the bubbly positivity of David’s optimism (his ‘sanguine’ disposition, as he puts it in that lovely European way_ helps him to engage students. “They say I have a lively delivery,” he adds wryly.

lent chess players, but they’re not usually great at holding the attention of six-year-olds. So does David has Asperger’s? Absolutely he does. But in his case it’s an ingredient in a rare personality cocktail. “I am different because I have Asperger’s, too – but I am sanguine.” It’s the perfect mix: the Asperger’s lends an obsessive concentration needed to be a brilliant chess player, while the bubbly positivity of David’s optimism (his ‘sanguine’ disposition, as he puts it in that lovely European way_ helps him to engage students. “They say I have a lively delivery,” he adds wryly.

David reaches into a folder and produces an exercise book: Step one of the six-step program he uses to turn kids into Grandmasters. “About ten people in Australia are at Step Six,” he says. Step one contains a few dozen pictures of chess boards, each with a different setup of pieces. Students are required to indicate the quickest routes of the pieces across the board. The one he shows me has been completed by a six-year-old boy; he can’t write properly yet, but he plays chess against 12-year-olds.

David’s early lessons are geared towards teaching the pupil how to be a good defender, which he sees as a player’s most vital attribute. “A lot of schools do it the other way around: they start with checkmate,” he says. “But how can you start with checkmate? Chess is like a soccer team. If your defences are right, then you can start attacking.”

And when the pieces start flying, it’s not uncommon for passions to spill over. During one game, David was beaten over the head with a chess board. This happened during a chess tournament, when his opponent came to the end of his two-hour time limit. “He was so angry at himself, that he sort of just went AARGHH!” says David, while standing up and swinging an imaginary chessboard at my head. Frightening. The player was banned for a year. “He’s not the only one,” he adds.

Aside from inciting the odd violent outburst, chess instils players with an ability to strategize and concentrate David says the game is especially beneficial for children with conditions such as ADHD, as it forces them to focus their attention. “Their world becomes 64 squares. Teachers will say, ‘He’s changed since he started playing chess! What happened?”

But most important, in David’s mind, is the enjoyment the game can bring. For him, it has meant a career, friends, world travel. “It’s my life,” he says.