Article by Chesslife Chess Coach Alex Jury

As children grow up many of them will seek out and participate in competition sport. This is both a natural and healthy development that should be encouraged. Competition sport boosts our self-esteem, improves our confidence and develops our ability to work in a team. Many schools recognise the value of sport and offer their children a variety of sporting opportunities.

Children, however, require guidance. In almost every school and sporting club, there is a team coach, their job being to teach and to train the players in their team. The importance of this position cannot be understated. Children are dependent on their coaches. They look to them for direction and instruction. It is therefore imperative that the coach for your children be the right man or woman for the job, as your child’s experience in sport will be largely influenced, for better or for worse, by their decisions and treatment of their teams.

So, what do you look for when looking for a coach? How do you pick the good coaches from the bad? There are many things to consider. Some of the most important of these have been compiled just below.

Number One: What Is Your Coach Trying To Accomplish?

Each coach has a different coaching method and personal style; no two are exactly the same. Most coaches, however, can be characterized by how they answer this very simple question: How do you define success?

The coaches who would answer that success is defined by their team winning are often referred to as Transactional Coaches.

The most common traits found in a Transactional Coach include:

- Making success the prime motivating factor, with their treatment of the players, parents and game reflecting this;

- Focusing their efforts in increasing the skill level and performance of individual players;

- Making team related decisions based on what will enhance the team’s likelihood of victory; and

- Training children to win. How this is achieved is often a secondary concern.

Transactional coaches are often seen as ‘good’ coaches, because they are able to produce visible results, these usually taking the form of success on the field, winning streaks, trophies and medals.

There is, however, another popular style of coaching, in which the coach does not see winning or even the sport itself as their primary concern. They see sport as a vehicle for children, not simply to have fun, but to also learn invaluable life lessons and skills. For these coaches, it is more important to inspire change in the player and not simply turn them into better players, but also better people. These coaches are referred to as Transformative Coaches.

The most common traits found in Transformative Coaches include:

- Developing the players to become better people;

- Wanting their players to improve in all aspects of life, on and off the field;

- Offering the team a role model, in him or herself;

- Building a team;

- Encouraging Teamwork;

- Treating players with respect and dignity, regardless of the outcome of a game; and

- Teaching life lessons – how to be humble in victory, courteous in defeat and the value of good sportsmanship.

Transformative Coaches have something of a mixed reputation. While they usually share a good rapport with their team and work hard on fostering a positive environment for their players, they do not always deliver the win that is expected of a ‘good’ coach. In fact, many Transformative Coaches downplay the importance of winning, especially in comparison to things like learning, participating and having fun. As such, Transformative Coaches are sometimes considered to be ‘bad’ coaches because their results do not always translate into wins on the field.

Finding out what your coach values is very important. On the surface, the Transactional Coaches seem ideal, because they promise and can deliver obvious results. However, as we shall find, these may not be the results children are looking for, or even need.

Number Two: What Do Your Children Want Out Of Sport?

When coaching children, we must remember why the child is there in the first place. Whatever our feelings towards competition sport, we must remember that this is ultimately about the children themselves. Why do they engage in sport? What do they hope to get out of it?

A study, conducted by George Washington University, sought to answer this very question. A youth soccer group were posed a series of questions about their participation in competition sport. When asked why they decided to engage in sport, 90% responded that they played sport to have fun. This is, however, a very broad term, and the children were further asked to provide explanations of what they considered ‘fun’ to be. They returned with 81 explanations, which were ranked in order of importance.

- Trying your best

- Being treated with respect by the coach

- Getting playing time

- Playing

- Getting along with their team

To these children, simply participating in the sport in a positive and encouraging environment was seen as the best part of a sporting experience. This isn’t to say that children didn’t at all value ‘winning’ or consider it a part of why they play sport. Winning was considered one part of what makes sport fun. The fact was, however, that ‘winning’ was rated at only 48 in terms of importance. Winning medals and trophies was rated at 67 and getting your picture taken was dead last at 81.

From this we can begin to understand that, for children at least, winning, and all that comes with it, is not a priority. Far from it, in fact. A coach needs to understand this and their treatment of the sport and the team needs to reflect this. If a coach is focused on winning, at the expense of things such as participation and a positive playing environment, then they run a serious risk of alienating their players from their sport.

Number Three: Does The Coach Engage Their Team?

Recent studies are showing a worrying trend: that many children will eventually drop out of youth sport programs. By the age of 13, a massive 70% of children will have dropped out of their sporting programs, with the likelihood of dropping out increasing by a third every year the child remains with the sport. So what triggers this sudden disinterest? Studies have suggested that much of this attitude can be attributed to the coach and their practices. When the coach emphasises that winning is the most important thing about sport, it can promote anxiety and depression for children when they fail.

Remember, only one team can win in competition sport. If the coach is demanding victory from his kids in every game, the pressure to always win can drive children away. Who wants to work, let alone play, in such a demanding environment?

It isn’t just the pressure to win that drives children from sport, but also a lack of playing time. When a coach is interested in fielding the best team they can, they can neglect or exclude the kids with lesser sporting capabilities. The key motivation for children participating in an activity is that they actually enjoy themselves. This doesn’t mean that coaches should abandon rules or scoring. The kids want to play sport! They want to learn it and become better players. But they also want to do it in a positive and inclusive environment that lets them enjoy it.

In the George Washington study, the same children surveyed in what they wanted out of sport were also asked what they wanted out of a coach. Their top five answers were:

- Respect and encouragement

- Positive role model

- Clear, consistent communication

- Knowledge of sport

- Someone who listens

Take note that, while the children did want a coach that had knowledge of sport, they did not prioritise a coach that would ‘lead them to victory’. If a coach does not encompass these values, they will not engage the children.

A win-obsessed coach will distance and estrange their players from sport. Children may want to win, but it is not a priority. Having fun, being respected and enjoying your time with the team clearly is; and the attitude of the coach needs to reflect that. If a coach does not do this; their attrition rates can be high, with kids missing out on sporting opportunities as a consequence.

Number Four: Win At All Costs. What Is The Real Lesson?

Assuming that your child stands by the Transactional Coach, what can they expect to learn from them? The Transactional Coach acts to improve a child’s performance. In return, they expect the child to win games. This ‘win at all cost’ mentality may drive a child to improve their game, but it also promotes harmful behaviour. Dr Kim Taylor found that the coaches who pressure children to succeed can result in children seeking ‘shortcuts’ in order to improve as fast as possible. These shortcuts don’t simply undercut the merits of hard work, patience and perseverance, but they can delve into unethical and self harming practices.

This was the experience of former National Football League defensive lineman, Joe Ehrmann. A victim of multiple Transactional Coaches, he was often pressured into winning, sometimes using unethical practices. One such coach coerced Joe into knocking out an opponent with a basketball. Joe did as he was told and broke the opposing player’s nose. Though Joe felt ashamed of what he did, neither this nor the injury the other player sustained mattered at all to the coach. He boasted that this was the way the game was meant to be played. His team had won. In his eyes, the end had justified the means.

Dr Alan Goldberg has often spoken out against such coaching methods. In one such report, mention was made of a tennis program that was, outwardly at least, highly successful. The team enjoyed a high success rate and the program was considered one of the best in the nation. The coach was driven to making his team the best. He demanded triumph from his team and would become abusive towards his players if they were, in his eyes, ‘uncommitted’. He forced his team to play even when they were injured, unconcerned that this would make their injuries worse. He became verbally abusive if his players lost a game or questioned his conduct. His players were miserable. Many of them abandoned sport altogether. Those who stayed reported suffering from self-directed anger and anxiety. The coach had impressed upon them they had to win. The pressure to meet this unreasonable demand drove his players to their breaking point.

Under these Transactional Coaches, respect, appreciation and esteem were conditional. To be appreciated you had to win. Nothing else mattered. It is hardly surprising that these coaches and their methods lead to high numbers of dissatisfied children, high mental stress and depression. Your children deserve better than this. A Transactional Coach may be able to make your child’s team the winning team, but the price to pay is simply too high.

Number Five: Lessons Above And Beyond The Field

As we can see, the Transactional Coach, while successful on the field, is not the ideal coach for a growing child. Attention to the needs of the child and their personal development as people, not just as players, is essential and a Transactional Coach simply cannot deliver this.

A Transformational Coach is not an easy coach to find, but is well worth the search. While they may not always be able to deliver victory in competition sport, they can do something so much more important – they can teach children how to be healthier and happier people. By providing a positive environment to learn in and a positive role model to learn from, the Transformative Coach inspires and motivates children to not only develop their talents in sport, but to develop as human beings.

Joe Ehrmann puts it best when he says, “Transformative coaches are other centred. They use their power and platform to nurture and transform players“. The sport itself is not the end goal. It is a vehicle for children to learn, develop and have fun.

As a parent, it can be difficult to find the right person for something as important as coaching your child. The important thing to remember is that the skill and quality of a coach should not be measured by their ability to deliver a win on the playing field. As the previous examples have demonstrated, the price to pay for the ‘winning’ coach can be all too high. It is better to aim for a coach who has their priorities on the betterment of their players, on and off the field and regardless of their individual ability. Those are the coaches that truly succeed.

So, what can you do?

Is your child losing interest in sport? Are they becoming less motivated to attend practice and games? Do they want to drop out? While some children will leave sport for alternate reasons, for others it will be because of how their lessons are being coordinated. Ask your child what happens during practice and how the coach treats them. Ask them why they are leaving or becoming less motivated. Attend a few practices yourself. See how the players treat each other and how the coach treats their team. Above all else, avoid judging the quality of a coach by his or her ability to produce a win. A coach centred on improving the child is far more important. Their results last far longer than any sporting season and are more valuable than any trophy.

Some Final Thoughts!

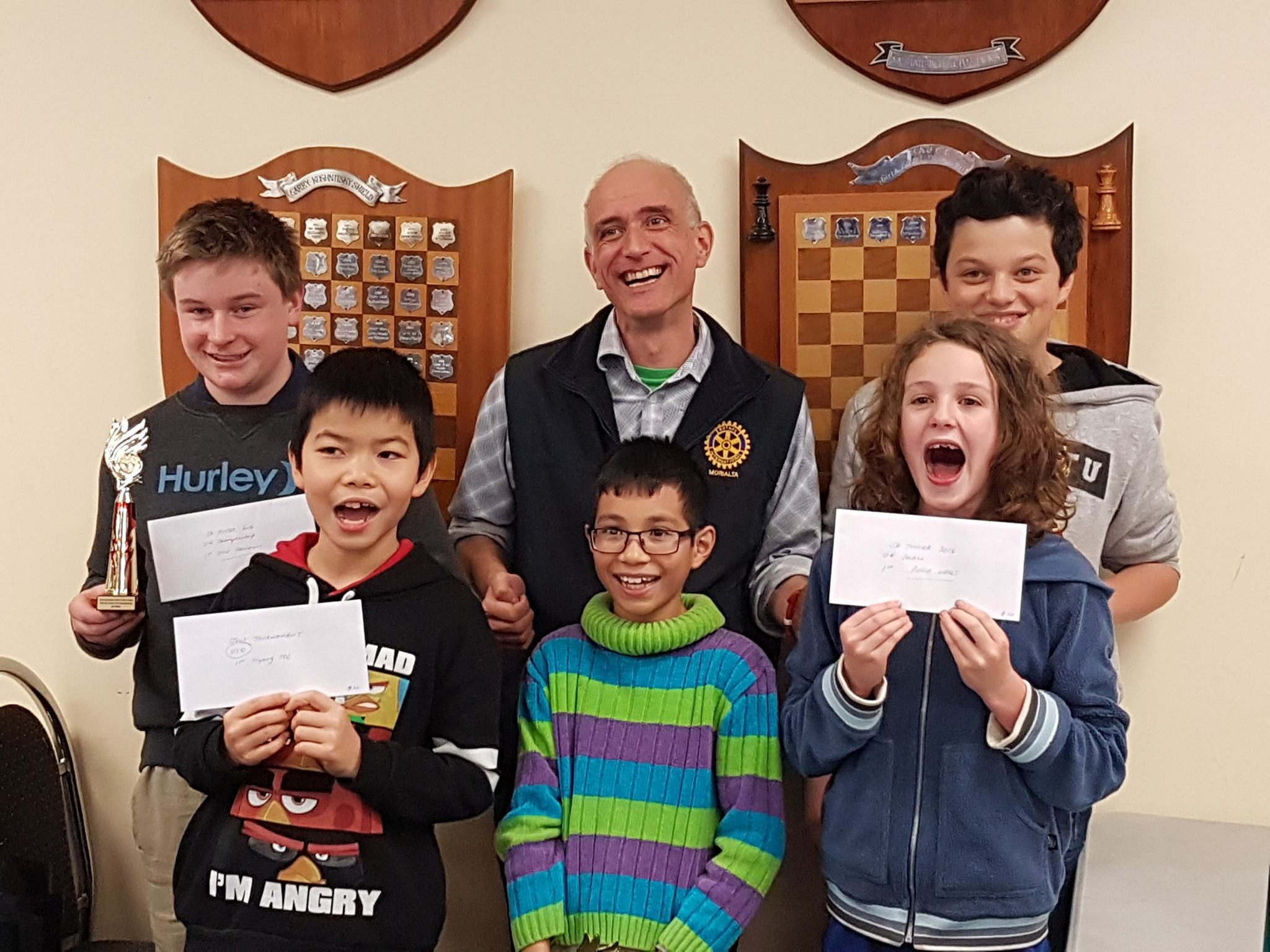

Here at Chesslife, we believe very strongly in the power of Transformative Coaching. We certainly celebrate achievements and train our students how to play their very best game of chess, but our core values go well beyond what a Transactional Coach tries to achieve. We see chess as so much more than a simple game or a distraction. There is so much that chess can teach us; and we consider it a priority that our trainees get everything they can out of our coaching lessons. We do not simply teach children how to play the game or even how to play the game well, but we teach them how to be better people.